The patient is a 35-year-old Caucasian female who presents with a chief complaint of “my liver tests are abnormal.” At her annual gynecology visit, routine labs were drawn. A complete blood count (CBC) was normal. A comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) revealed mild elevation of the aspartate aminotransferase at 52 U/L and alanine transaminase at 64 U/L. There was a significant elevation of the alkaline phosphatase at 320 U/L. The total bilirubin and albumin were normal. A CBC and CMP last done 3 years ago were normal.

The patient is a 35-year-old Caucasian female who presents with a chief complaint of “my liver tests are abnormal.” At her annual gynecology visit, routine labs were drawn. A complete blood count (CBC) was normal. A comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) revealed mild elevation of the aspartate aminotransferase at 52 U/L and alanine transaminase at 64 U/L. There was a significant elevation of the alkaline phosphatase at 320 U/L. The total bilirubin and albumin were normal. A CBC and CMP last done 3 years ago were normal.

She is asymptomatic. She has no chronic medical problems. She does not take any medication. She drinks < 5 to 6 alcoholic drinks per week. Her body mass index is normal. She has no risk factors for viral hepatitis. She denies a family history of liver disease. Her father has Hashimoto’s disease.

What is the most likely etiology for the elevated alkaline phosphatase?

A) Hepatitis A

B) Hemochromatosis

C) Primary biliary cholangitis

D) Hepatitis B

The correct answer is C, primary biliary cholangitis (PBC).

Practice Pearls

PBC is a rare disease. More than 80 percent of people with PBC are female. The prevalence of PBC is more common in the United States and Northern Europe compared to other parts of the world.

The etiology of PBC is unknown. It is considered an autoimmune disease. It is unclear what initiates the T-cell attack on small bile duct epithelial cells.1 Environmental causes have been postulated, including infectious etiology, toxins and medication. Genetic studies have not revealed an exact genetic link. There is a weak association between PBC and haplotypes HLA-DR8 and HLA-DPB1.1

PBC is a progressive disease, potentially spanning several decades. The rate of progression varies among individuals. Over recent years, PBC has been diagnosed at an earlier stage and many patients respond well to therapy.2

Most patients are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Fatigue is the most common symptom. Daytime somnolence is seen in some patients and could diminish quality of life. Pruritus varies among patients, from mild to intractable and very bothersome. Pruritus is typically worse at night and may be associated with dry skin and hot, humid weather.1

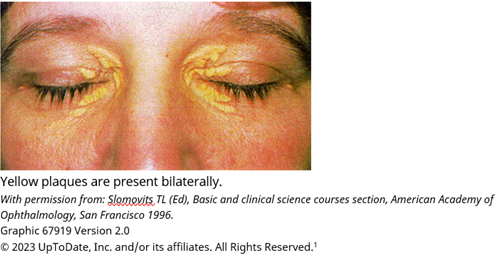

Physical examination findings may include hyperpigmentation, xanthomas, xanthelasmas (Figure 1) and jaundice.1

Hepatosplenomegaly may be seen, especially in disease progression.

Consider PBC as a diagnosis in patients (especially females in their fifth to sixth decade of life) with an elevated alkaline phosphatase and no evidence of biliary obstruction, unexplained pruritus and unexplained jaundice in advanced disease.

A diagnosis of PBC is established if there is no biliary obstruction and at least two of the following criteria are present: an alkaline phosphatase 1.5 times the upper limits of normal, presence of antimitochondrial antibodies (AMAs) at a titer of >1:40 or histologic evidence of PBC.1

Liver biopsy is not required to establish the diagnosis of PBC; however, it could provide useful clinical information. Liver biopsy is reasonable if PBC is suspected, yet the AMA is negative. It can also be helpful to exclude concomitant diseases such as autoimmune hepatitis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.2

Histologic findings are divided into five stages: 0 to 4 (Figure 2).

Stage 0: Normal liver

Stage 1: Inflammation and/or abnormal connective tissue confined to portal areas

Stage 2: Inflammation and/or fibrosis confined to portal and periportal area

Stage 3: Bridging fibrosis

Stage 4: Cirrohsis1

Noninvasive tests to measure fibrosis, such as FibroScan or FibroSURE, can be helpful in patients with PBC to determine the extent of disease. If there is evidence of advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis, additional testing may be indicated.

Initial therapy for all patients is weight-based ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), using 13 to 15 mg/kg administered orally, twice daily. Patients who do not respond to UDCA (alkaline phosphatase above the upper limits of normal after one year) and are without cirrhosis can be treated with combined therapy using obeticholic acid (OBA) and UDCA.1,2 OBA must be used with caution in patients with advanced fibrosis, with appropriate dose reduction.

Pruritus is managed based on the severity of symptoms. For mild pruritus, emollients could help. For nocturnal symptoms causing insomnia, antihistamines may help. Patients with moderate to severe symptoms could be treated with cholestyramine 4 grams orally two to three times daily, rifampin 150 mg orally twice daily, with potential to increase to 300 mg taken by mouth twice daily (if cholestyramine fails), and in some patients, sertraline, naltrexone and phenobarbital have been helpful.1,2

Long-term monitoring includes liver biochemical and function tests every three to six months, vitamin A and D levels and prothrombin time yearly, thyroid-stimulating hormone, bone densitometry every two years, and screening for gastroesophageal varices and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with cirrhosis.1

Complications of PBC include metabolic bone disease, hypercholesterolemia, fat malabsorption and cirrhosis, including portal hypertension and hepatocellular carcinoma.1

Figure 1: Xanthelasmas

Figure 2: Pathology Stages of PBC

![(A) Stage 1 with portal inflammation and a florid ductal lesion; hematoxylin-eosin, magnification 20x. (B) Stage 2 PBC with portal inflammation, focal interface hepatitis, and bile ductular proliferation; hematoxylin-eosin, magnification 40x. (C) Stage 3 PBC with bridging inflammation; hematoxylin-eosin, magnification 20x. (D) Stage 4 PBC showing cirrhosis with ductopenia; hematoxylin-eosin, magnification 20x. Courtesy of Dr. Monica Tulia Garcia-Buitrago. [Correction added on December 18, 2018, after first online publication: Acknowledgement for Dr. Monica Tulia Garcia-Buitrago was added.]](/images/default-source/page-layout-images/pathology-stages-of-pbc.png?sfvrsn=f885315c_1)

Sarah Enslin, PA-C

University of Rochester Medical Center

Rochester, NY

Andrea Gossard, APRN, CNP

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, MN

Joseph Vicari, MD, MBA, FASGE

Rockford Gastroenterology Associates

Rockford, IL

Sarah Enslin, PA-C, is a physician assistant at the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, NY. Sarah serves on several national GI committees and is a member of the ASGE Practice Operations Committee.

Andrea Gossard, APRN, CNP, is a certified nurse practitioner, clinical associate in gastroenterology and hepatology, and an associate professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN. She has authored 43 peer-reviewed articles, five book chapters and over 50 abstracts on liver disease.

Joseph Vicari, MD, MBA, FASGE, joined Rockford Gastroenterology in 1997 and has served as managing partner. He previously served as chair of the ASGE Practice Operations Committee and currently serves as councilor on the ASGE Governing Board.

- UpToDate Pathogenesis of primary biliary cholangitis (primary biliary cirrhosis). Clinical manifestations, diagnosis and prognosis of primary biliary cholangitis (primary biliary cirrhosis). Overview of the management of primary biliary cholangitis (primary biliary cirrhosis). Retrieved from the UpToDate.com website, https://www.uptodate.com

- Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, Levy C, Mayo M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2018 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2019;69: 394-419.