A 69-year-old woman is evaluated for longstanding dysphagia to solids. She reports daily episodes of dysphagia for more than five years and prior endoscopies have been unrevealing. The last endoscopy three years ago found shallow ulceration in the mid esophagus and a stricture. Esophageal dilation was performed, and she was placed on a proton pump inhibitor. She reports difficulty chewing her food due to painful oral lesions. In addition, she also reports oral and vaginal lesions. She denies a history of food bolus impactions, seasonal allergies or asthma.

What is the most likely diagnosis to consider

- Heartburn

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Esophageal lichen planus

- Esophageal adenocarcinoma

The correct answer is C, esophageal lichen planus.

Differential diagnoses to consider:

- Pill esophagitis

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Fungal infections

- Viral infections

- Bullous pemphigoid

- Pemphigus vulgaris

- Crohn’s disease

- Chagas disease

- Graft-versus-host disease

Practice Pearls

Epidemiology

Lichen planus is a chronic mucocutaneous inflammatory disease. The pathogenesis of lichen planus is only partially understood but it appears to be an autoimmune disease.5 Hepatitis C infection as well as certain medications have also been implicated as a possible etiology.3 Cutaneous lichen planus involving the skin and genital regions is the most common. It affects about 2 percent of the population and is predominantly seen in middle-aged females.1,5,8 Esophageal lichen planus is less common but likely underrecognized.7

Clinical Manifestations

The most common clinical manifestation is dysphagia, occurring in 80 to 100 percent of patients with esophageal lichen planus. Odynophagia may also occur. Less common symptoms include heartburn, regurgitation, chronic cough, hoarseness and weight loss.1,3,6,8

Evaluation

There is an association between oral, vaginal and esophageal lichen planus. A physical examination including a good oral examination can guide in the diagnosis of esophageal lichen planus. Patients with oral lichen planus often complain of oral discomfort or pain and can have evidence of lichen planus on exam, including fine white buccal lines (Wickham striae) and mucosal ulceration1 (Image 1).

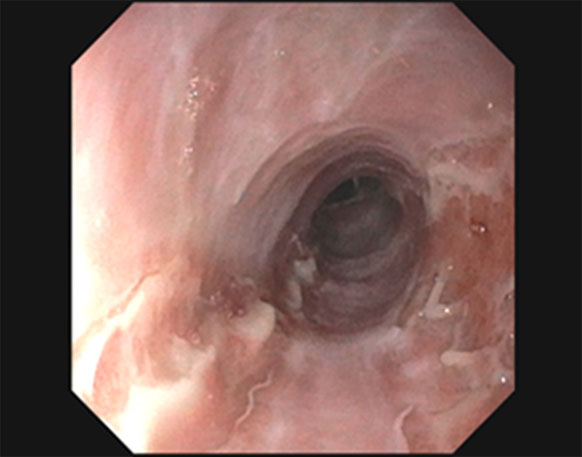

Common endoscopic esophageal features include strictures, rings, mucosal sloughing, a white lacy appearance and hyperemic lesions1,6,8 (Image 2). Histopathologic findings include lymphocytic infiltration, hyperkeratosis and degenerated keratinocytes (Civatte bodies).2,6 Radiographically, proximal esophageal strictures are commonly seen (Image 3), but in severe cases, the entire esophagus can be involved.2,5

Management

There are no accepted guidelines regarding management of esophageal lichen planus. Studies show that topical steroids, such as budesonide, are effective in up to 74 percent of patients. Intralesional injection of triamcinolone has also been described. Systemic steroids can be considered to induce a rapid response but are a less favorable option for long-term maintenance therapy. Severe cases not responding to topical steroids may require systemic immunosuppressants.1,3,6

Dilation plays a key role in the treatment of symptomatic esophageal lichen planus and should be performed in conjunction with anti-inflammatory therapy to reduce ulceration and recurrent stenosis.1

Self-dilation can be effective for many etiologies of benign esophageal strictures and can be considered in highly selected lichen planus patients, especially those with severe refractory strictures.7

Although esophageal lichen planus is a rare condition, there is a risk of development of squamous esophageal carcinoma. Some studies suggest that the risk can be as high as 6.1 percent in patients with esophageal lichen planus.4

Image 1: White buccal lines (Wickham striae) and mucosal ulceration |

|

Image from personal library of Sarel Myburgh |

Image 2: Common endoscopic esophageal features include strictures, rings, mucosal sloughing, a white lacy appearance and hyperemic lesions |

|

Image from personal library of Sarel Myburgh |

Image 3: Radiographically proximal esophageal strictures |

|

Image from personal library of Sarel Myburgh |

Lichen Planus of the Esophagus: What Dermatologists Need to Know9

| Clinical Features | Radiological Features | Endoscopic Features |

|---|

| Middle-aged, female | Most common are proximal strictures | Ulcerated esophageal mucosa |

| Oral lesions — gumline or buccal mucosa | Involvement of entire esophagus in severe cases | White plaques

Coexisting candida |

Genital lesions

Skin lesions | Mucosal irregularity | Strictures with fragile and sloughing mucosa when dilating |

Efficacy of Topical Steroid-Based Therapies10

| Key Diagnostic Tests | Treatment |

|---|

| Esophagram | First line: Topical budesonide

Intralesional steroid injection |

| EGD + biopsies | Second line: Systemic steroid therapy |

Biopsies of oral or genital lesions

Involve dermatology | Third line: Immunomodulator therapy |

| Esophageal biopsies can show lymphocytic infiltration, hyperkeratosis or Civatte bodies (highly suggestive but only seen in about <30 percent) | Endoscopic dilation

Self-dilation in highly selected cases |

References

- Decker A, Schauer F, Lazaro A, et al. Esophageal lichen planus: Current knowledge, challenges and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:5893-5909. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i41.5893. PMID: 36405107; PMCID: PMC9669830.

- Fox LP, Lightdale CJ, Grossman ME. Lichen planus of the esophagus: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:175-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.029. Epub 2011 May 4. PMID: 21536343.

- Katzka DA, Smyrk TC, Bruce AJ, Romero Y, Alexander JA, Murray JA. Variations in presentations of esophageal involvement in lichen planus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:777-82. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.04.024. Epub 2010 May 13. PMID: 20471494.

- Ravi K, Codipilly DC, Sunjaya D, Fang H, Arora AS, Katzka DA. Esophageal lichen planus is associated with a significant increase in risk of squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1902-1903.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.018. Epub 2018 Oct 17. PMID: 30342260.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. Lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1103641. PMID: 22356325.

- Podboy A, Sunjaya D, Smyrk TC, et al. Oesophageal lichen planus: the efficacy of topical steroid-based therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:310-318. doi: 10.1111/apt.13856. Epub 2016 Nov 17. PMID: 27859412.

- Qin Y, Sunjaya DB, Myburgh S, et al. Outcomes of oesophageal self-dilation for patients with refractory benign oesophageal strictures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:87-94. doi: 10.1111/apt.14807. Epub 2018 May 21. PMID: 29785713.

- Quispel R, van Boxel OS, Schipper ME, et al. High prevalence of esophageal involvement in lichen planus: a study using magnification chromoendoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:187-93. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1119590. Epub 2009 Mar 11. PMID: 19280529.

- Fox LP, Lightdale CJ, Grossman ME. Lichen planus of the esophagus: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:175-183.

- Podboy A, Sunjaya D, Smyrk TC, et al. Oesophageal lichen planus: the efficacy of topical steroid-based therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:310-318.

| Sarel Myburgh, APRN, CNP, is a nurse practitioner specialist with over nine years of diverse experience in Rochester, Minnesota, and affiliates with many hospitals in the Mayo Clinic Health System. He currently serves on the ASGE APP Committee. |

| John Martin, MD, FASGE, is a full-time practicing gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. In addition to his clinical practice, Dr. Martin’s interests center on endoscopy unit operations and efficiency, technological innovations in endoscopy, and endoscopic training and simulation in hands-on training and education. He has served on numerous ASGE committees and previously served on the ASGE Governing Board. Dr. Martin currently serves on the ASGE Practice Operations Committee and the ASGE APP Committee. |