Subjective

History of Present Illness:

N.O. is a 29-year-old male presenting with six weeks of generalized pruritus. He initially attributed the generalized pruritus to dry skin; however, over the past two weeks, the pruritus has intensified and become persistent. Over these past two weeks, he reports fleeting episodes of subjective fever, lasting no more than an hour each time. N.O. reports living an active lifestyle but has recently noticed mild fatigue after his daily runs and feeling more tired throughout the day. N.O. denies nausea, vomiting, chills, night sweats, jaundice, chest or abdominal pain, joint pain, back pain, shortness of breath, blood in the stools, pale stools, dark stools or urine, decrease in appetite or weight loss.

Medications:

None

Allergies:

None

Past Medical History:

Ulcerative pancolitis; diagnosed at age 21; treated with steroids and 5 ASA initially, but colitis symptoms have quiesced without recurrence

Past Surgical History:

Appendectomy at age 15

Social History:

Has worked as an in-house accountant for a large pharmaceutical company for 7 years

Consumes alcohol socially

Denies tobacco use

Denies travel outside of the U.S.

Family History:

Married to wife for eight years, who is without medical problems

Has 7-year-old fraternal twins who are without medical problems

Objective

Vital Signs:

Afebrile, hemodynamically stable

Physical Examination:

Normal physical examination

Diagnostics

Labs:

CBC and differentials within normal limits

AST 58, ALT 62, ALP 223, TBIL 1.5

As the gastroenterology and hepatology advanced practice provider (APP) specialist in the group, the patient is referred to you for further workup.

The most likely etiology of his liver enzyme elevations is:

- Hepatitis A

- Hepatitis C

- Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC)

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

- Autoimmune hepatitis

Answer is D: PSC

The patient has no risk factors for hepatitis A and C. Hepatitis serologies and autoimmune markers are often ordered to initiate workup for viral and autoimmune etiologies of liver disease but will not provide a diagnosis of PSC. PBC is female-predominant and is not associated with inflammatory bowel disorder (IBD). PSC is highly associated with IBD, and pruritus can be severe in this cholestatic disorder. Autoimmune hepatitis typically presents with high aminotransferase levels and is not as strongly associated with IBD.

What would be the first test of choice to confirm the presence of PSC?

- Liver biopsy

- Ultrasound of the liver

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

- Autoimmune markers

Answer is D: MRCP

Liver biopsy has limited sensitivity for diagnosing PSC. Ultrasound will not resolve the more subtle bile duct irregularities or milder strictures that can manifest in less severe PSC. ERCP is invasive with a substantially higher risk of adverse events than MRCP. MRCP is preferred over ERCP for PSC diagnosis and surveillance. However, if tissue acquisition or treatment of strictures is required, ERCP is indispensable. Autoimmune markers are not diagnostic for PSC.

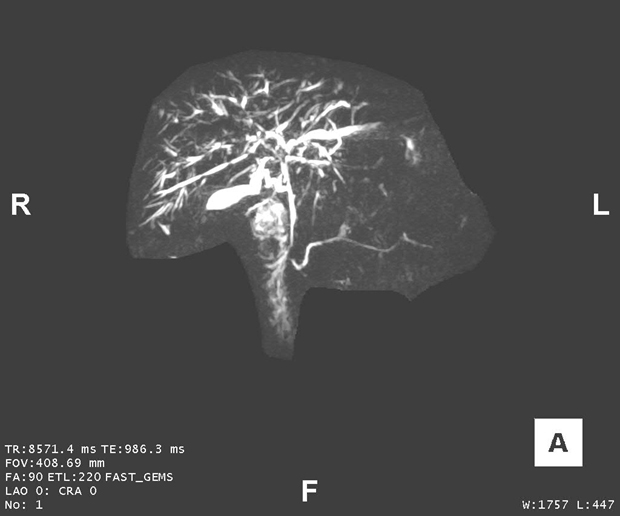

Here is a key image of the MRCP (figure 1)

Image from the library of Mayo Clinic

Figure 1. MRCP image demonstrating PSC strictures in the bile duct. Note strictures of the intrahepatic ducts and the perihilar extrahepatic duct, with prestenotic dilatation, particularly of the left hepatic duct.

Practice Pearls: PSC

Epidemiology

PSC is an autoimmune, progressive cholestatic disease characterized by chronic inflammation and fibrosis (scarring) of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts. The progression of PSC is variable and irreversible, leading to multifocal bile duct strictures and, ultimately, cirrhosis and liver failure. PSC is associated with an elevated risk of hepatobiliary malignancies, including cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), gallbladder carcinoma and colon cancer. For example, the incidence of CCA with a PSC diagnosis is approximately 0.5-1.5 percent per year, with a lifetime risk of about 20 percent. Thus, close surveillance for early detection of these malignancies is indispensable. Life expectancy with a PSC diagnosis is reduced by about 30 years, and transplant-free survival is approximately 10 to 20 years after the initial diagnosis. The etiology of PSC remains unclear, but there is a suspected combination of genetic predispositions and environmental risk factors that lead to PSC and its progression. PSC is strongly associated with IBD, with ulcerative colitis (UC) presenting in more than 75 percent of cases. Conversely, only a minority (1-15 percent) of patients with IBD have PSC. The prevalence of PSC is greater in men, nonsmokers and patients with a history of an appendectomy as well as those with pancolitis versus left-sided-only UC.

The classic appearance on imaging (i.e., cholangiography) of the bile ducts with PSC is multifocal narrowing with intervening segments of prestenotic ductal dilatation. This appearance is often described as a beaded pattern. Focal strictures of the extrahepatic bile ducts or larger hepatic ducts are often referred to as “dominant strictures,” and strictures that cause obstructive cholestasis or bacterial cholangitis are termed “relevant strictures.” A less common variant of PSC is known as “small-duct PSC,” which is characterized by typical cholestatic and biochemical features of PSC, but cholangiogram findings demonstrate normal bile ducts.

Clinical Manifestations

At the time of diagnosis, patients with PSC may be asymptomatic, with PSC often identified through elevated ALP levels on routine labs. Patients with PSC and biliary strictures causing biliary obstruction and cholestasis may present with variable symptoms of fever, chills, jaundice, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, fatigue, pruritus and recurrent episodes of ascending bacterial cholangitis that can lead to bacteremia and sepsis. Chronic biliary obstruction progresses to cirrhosis with portal hypertension and synthetic dysfunction.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PSC is typically confirmed through cholangiography, revealing characteristic bile duct strictures and dilations. Noninvasive imaging of the biliary system with MRCP — an MRI protocol to optimally visualize the biliary tree — is the test of choice. An MRCP has high sensitivity for visualizing bile duct abnormalities.

Management

There is currently no treatment proven to alter the disease course of PSC or improve transplant-free survival. Management focuses on symptom control and surveillance of hepatobiliary malignancies. If focal large duct strictures are demonstrated on imaging, an ERCP is imperative to obtain intraductal tissue sampling for cytology and FISH to exclude CCA. If biliary strictures result in obstruction and symptoms, balloon dilation with or without placement of biliary stents can be a useful treatment delivered via ERCP. For advanced PSC, a liver transplant is the only definitive treatment. However, in about 25 percent of cases, recurrence in the graft can occur. Screening recommendations for hepatobiliary malignancies in patients with PSC include: 1) annual MRI/MRCP with or without serum CA 19-9 for CCA and gallbladder carcinoma; 2) abdominal ultrasound twice a year with gallbladder polyps 8 mm in size or less, with cholecystectomy recommended when polyps exceed 8 mm; and 3) surveillance colonoscopies with biopsies in patients with PSC and concomitant IBD starting at age 15 years and repeated at one- to two-year intervals.

Case study takeaway: The APP caring for N.O. with a history of IBD, new and persistent pruritus and fatigue, and an elevated ALP should have a high level of suspicion for the possibility of PSC, prompting the APP to pursue further diagnostic workup and management.

References

- Bowlus CL, Arrivé L, Bergquist A, et al. AASLD practice guidance on primary sclerosing cholangitis and cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2022;77:659-702. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.32771

- Dyson JK, Beuers U, Jones DEJ, Lohse AW, Hudson M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet. 2018;391:2547-2559. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30300-3

| Kathryn Swenson, APRN, CNP, DNP, MSN, is a nurse practitioner in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. She specializes in advanced endoscopy. |

| John A. Martin, MD, FASGE, is a full-time practicing gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. In addition to his clinical practice, Dr. Martin’s interests center on endoscopy unit operations and efficiency, technological innovations in endoscopy, and endoscopic training and simulation in hands-on training and education. He has served on numerous ASGE committees and previously served on the ASGE Governing Board. Dr. Martin currently serves on the ASGE Practice Operations Committee and the ASGE APP Committee. |