A 40-year-old woman presented for evaluation of dysphagia. Symptoms began three years ago and recently worsened. She has dysphagia to solids and liquids with almost every meal. She describes a sensation of “food or liquids stacking up in my esophagus.” Some episodes of dysphagia are associated with mild substernal chest pressure. She will walk around, raise her chin and move her shoulders backward in an attempt to alleviate the discomfort. She has rare episodes of nocturnal oral regurgitation, denies weight loss, GI bleeding and heartburn, and does not use alcohol or tobacco. She takes levothyroxine for hypothyroidism. There is no other medical history and no family history of GI cancers. She denies seasonal allergies.

What is the most likely etiology for this patient’s symptoms?

A) Schatzki’s ring

B) Eosinophilic esophagitis

C) Primary achalasia

D) Esophageal adenocarcinoma

The correct answer is C, primary achalasia.

Practice Pearls

Achalasia results from progressive degeneration of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus of the esophageal wall, leading to failure of relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and loss of peristalsis in the distal esophagus.1,2

The global incidence ranges from 0.003 to 1.63 per 100,000 persons per year, with a prevalence of 1.8 to 12.6 persons per year. Achalasia is a rare diagnosis, affecting 20,000 to 40,000 persons in the United States.2 Men and women are equally affected.

The etiology of primary achalasia is unknown. Secondary achalasia is due to diseases that cause esophageal motor disorders similar or identical to primary achalasia (e.g., gastric carcinoma, Chagas Disease and sarcoidosis).1

The most common clinical manifestations include dysphagia to solids (91%) and liquids (85%) and regurgitation of food or saliva.1 Additional symptoms may include substernal chest pain, heartburn and, less often, weight loss and hiccups.

Achalasia is diagnosed by high-resolution esophageal manometry. Typical findings include impaired relaxation of the LES, as evidenced by an elevated integrated relaxation pressure as well as abnormal peristalsis. Manometry findings of achalasia can be classified into three distinct subtypes: type I, with complete absence of peristalsis; type II, with pan-esophageal pressurization; and type III, with spastic peristalsis.3

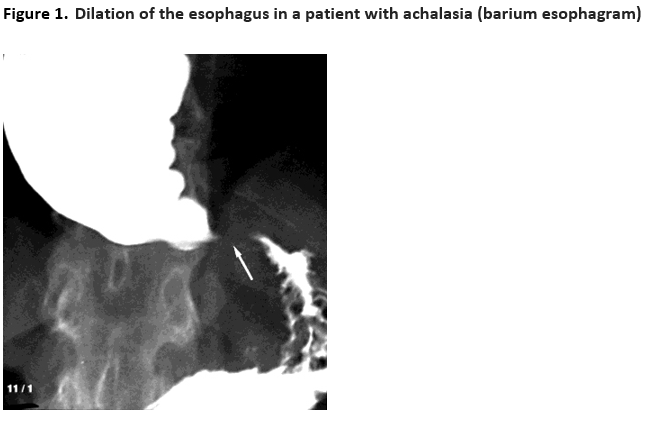

Barium esophagram typically demonstrates dilation of the esophagus with smooth tapering to a narrowed gastroesophageal junction (“bird-beak” appearance) and delayed emptying of barium (Figure 1).1

Upper endoscopy can be unremarkable but may reveal a dilated esophagus, residual food material in the lumen and a puckered lower esophageal sphincter that does not open spontaneously, resulting in resistance to scope passage with a “pop” felt by the endoscopist once traversed with the scope.1

Treatment of achalasia is focused on decreasing the LES pressure. Temporary relief can be achieved with endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin into the LES, typically lasting for three to six months. Definitive therapeutic options include pneumatic dilation with a large-diameter balloon under fluoroscopic guidance, peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) or Heller myotomy (laparoscopic or open surgery) with partial fundoplication. The treatment choice should be guided by high-resolution manometry findings, patient age, comorbidities, expertise availability and shared decision-making with the patient.4 Pharmacological therapies are generally ineffective, but they may include phosphodiesterase inhibitors or calcium channel blockers, which can be considered in patients unable to tolerate more invasive therapies.4

POEM, Heller myotomy with partial fundoplication, and pneumatic dilation are effective treatments for patients with type I and type II achalasia, whereas evidence suggests POEM is more effective in type III achalasia. Botulinum injection is reserved for patients thought not to be candidates for more definitive therapy due to their age and/or comorbidities.4

Technical success after definitive achalasia therapy is high, but it is important to counsel patients that POEM is associated with a higher risk of reflux esophagitis (41%-44%) compared to pneumatic dilation (7%) and Heller myotomy with partial fundoplication (9%-29%).4

Barium esophagram in a 62-year-old man demonstrates a dilated, barium-filled esophagus with a region of persistent narrowing (arrow) at the gastroesophageal junction, producing the so-called bird's beak appearance. Achalasia was confirmed with manometry and the patient underwent successful dilation of the esophagus.

Courtesy of Jonathan Kruskal, MD.

Graphic 54252 Version 4.0

© 2023 UpToDate, Inc. and/or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved.1

Sarah Enslin, PA-C

University of Rochester Medical Center

Rochester, NY

John Martin, MD, MBA, FASGE

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, MN

Sarel Myburgh, APRN, CNP

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, MN

Joseph Vicari, MD, MBA, FASGE

Rockford Gastroenterology Associates

Rockford, IL

Sarah Enslin, PA-C, is a physician assistant at the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, NY, with over 10 years of experience as a practicing PA in GI. Sarah serves on several national GI committees and is a member of the ASGE Practice Operations Committee.

John Martin, MD, MBA, FASGE, is a full-time practicing gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. In addition to his clinical practice, Dr. Martin’s interests center on endoscopy unit operations and efficiency, technological innovations in endoscopy, and endoscopic training and simulation in hands-on training and education. He has served on numerous ASGE committees and previously served on the ASGE Governing Board. Dr. Martin currently serves on the ASGE Practice Operations Committee.

Sarel Myburgh, APRN, CNP, is a nurse practitioner specialist with over seven years of diverse experiences in Rochester, Minn., and affiliates with many hospitals in the Mayo Clinic Health System.

Joseph Vicari, MD, FASGE, joined Rockford Gastroenterology in 1997 and has served as managing partner. He previously served as chair of the ASGE Practice Operations Committee and currently serves as councilor on the ASGE Governing Board and co-chair of the ASGE APP Task Force.

- UpToDate Achalasia: Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations and diagnosis. Retrieved from the UpToDate.com website, https://www.uptodate.com

- Vaezi MF, Pandalfino JE, Yadlapati RH, Greer KB, Kavitt, RT. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:1393-1411

- Yadlapati R, Kahrilas PJ, Fox MR, et al. Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0 ©. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021;33:e14058

- UpToDate Achalasia: Overview of the treatment of achalasia. Retrieved from the UpToDate.com website, https://www.uptodate.com